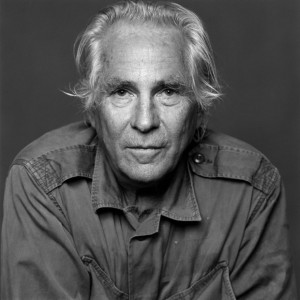

Ten years ago, I stood on Brian Evenson’s front porch in Providence, R.I., minutes away from Brown University where he taught. He asked me to pick him up. The recycling bin was out and I made a mental note of the organic cereal boxes inside. This is what he eats, I thought. The writer who sent all of Utah into a tizzy eats organic breakfast cereal. I had been reading Evenson for years. I read his novel Father of Lies in one sitting. When I read Altmann’s Tongue I couldn’t believe he was a Mormon (now an ex-Mormon). And the stories in The Wavering Knife were some of the best American short stories I’d read since I discovered Richard Yates in grad school. It was a sunny, but cold March New England day. The dog barked when I knocked. “I’ll be out in a minute,” Evenson said. “The dog will freak out if I let you in. Sorry.” And then there he was. Brian Evenson. One of the nicest guys I’ve ever met.

Ten years ago, I stood on Brian Evenson’s front porch in Providence, R.I., minutes away from Brown University where he taught. He asked me to pick him up. The recycling bin was out and I made a mental note of the organic cereal boxes inside. This is what he eats, I thought. The writer who sent all of Utah into a tizzy eats organic breakfast cereal. I had been reading Evenson for years. I read his novel Father of Lies in one sitting. When I read Altmann’s Tongue I couldn’t believe he was a Mormon (now an ex-Mormon). And the stories in The Wavering Knife were some of the best American short stories I’d read since I discovered Richard Yates in grad school. It was a sunny, but cold March New England day. The dog barked when I knocked. “I’ll be out in a minute,” Evenson said. “The dog will freak out if I let you in. Sorry.” And then there he was. Brian Evenson. One of the nicest guys I’ve ever met.

Before I interviewed Brian, I told a friend that the feeling I got when I read an Evenson story is the same feeling I get when I see a photograph of punk rocker G.G. Allin. Allin started every show by pounding his head with his microphone until all the scabs (from the previous show) on his head were bleeding. And then he took off all his clothes.

Before I interviewed Brian, I told a friend that the feeling I got when I read an Evenson story is the same feeling I get when I see a photograph of punk rocker G.G. Allin. Allin started every show by pounding his head with his microphone until all the scabs (from the previous show) on his head were bleeding. And then he took off all his clothes.

It’s been ten years since the interview, and I can’t remember why I didn’t publish it at the time. I’ve read it a few times over the years and never known quite what to do with it. The longer this went on the more embarrassed I was to be sitting on the interview. Then I read Adrian Van Young’s article in the New Yorker, “The Dark Fiction of an Ex-Mormon Writer,” and I thought I should publish the interview on my blog. Brian consented.

In the ten years since this interview, Brian has continued to publish important and original American books—among them The Open Curtain, Last Days, Immobility, and his latest, a collection of stories called A Collapse of Horses. He no longer teaches at Brown, having just taken a position at CalArts. He’s one of our most prolific and important American writers and I’m thrilled he’s getting recognized as such. Without further adieu, here is my interview with my favorite writer, Brian Evenson, ten years later. It is long and unedited, we go deep into the Mormon weeds, and there really is no ending (it just stops). I hope you enjoy it.

In the ten years since this interview, Brian has continued to publish important and original American books—among them The Open Curtain, Last Days, Immobility, and his latest, a collection of stories called A Collapse of Horses. He no longer teaches at Brown, having just taken a position at CalArts. He’s one of our most prolific and important American writers and I’m thrilled he’s getting recognized as such. Without further adieu, here is my interview with my favorite writer, Brian Evenson, ten years later. It is long and unedited, we go deep into the Mormon weeds, and there really is no ending (it just stops). I hope you enjoy it.

*

AS: Now that you’re technically not Mormon anymore how do you respond to the label “Mormon-American Writer?

BE: As with something like Judaism there is a high-cultural element to being Mormon and so even if one is no longer religiously Jewish one is still very much culturally Jewish. And I think the same is true of Mormonism. It’s a very intense culture to grow up in. You grow up in a very particular way, you grow up thinking about the world in a way that is pretty unique and maybe even strange to a lot of people. So I guess that’s what I would say about that. Religiously, I’m not Mormon anymore, I’ve made a real effort to separate myself out from that, but culturally all that went into my upbringing and went into it very intensely and I very actively tried to couple that with things from the larger world, the outside world, but that’s still something that is very much part of me and that really even controls the way I think about language or the way in which I talk sometimes.

AS: Could you talk a little bit about how books figured into your home, what kinds of books were there, and even your parents relationship with books.

BE: We all read a lot. My mother used to read all the time; she kind of would read so much that she almost ignored us sometimes. She was really into mystery novels, and would read them obsessively, but then would also read things that were more literary. Same with my father. So we grew up in a house where we would go on vacation to the beach and everyone sit in the house and read. So books were always a big part of things. I grew up reading science fiction and fantasy novels and that sort of thing. Then, at a particular moment, my father started to—he was an administrator at Brigham Young University—and he started to read their general education books and got very interested in some of those and began to give some of those to me. I think the most important thing was when I was around 13 or 14 he brought home a copy of The Basic Kafka and sat down and read a story kind of with me and then talked about it and then gave me the book. That’s the moment I can really identify my reading habits as changing. So I went in the course of just a year or two from reading things like Roger Zelazny and Anne McCaffrey to reading Kafka and that led me to people like Beckett and those sorts of things. There was a decent used bookstore in Provo that just happened to have a lot of Grove Press books and so I just started reading basically Grove Press books. I started reading these books, mostly plays by people like Beckett and Ionesco, and who knows who else and that suddenly made me think about, it brought me in connection to the larger literary world. But I really just cobbled it together. I read things at random; I kind of made my own parameters, which was I was going to read everything that this press has done and went from there to reading other things. And that’s kind of the way I’ve constructed it, I’ve just read at random and allowed things to influence me just coming from wherever they come from.

BE: We all read a lot. My mother used to read all the time; she kind of would read so much that she almost ignored us sometimes. She was really into mystery novels, and would read them obsessively, but then would also read things that were more literary. Same with my father. So we grew up in a house where we would go on vacation to the beach and everyone sit in the house and read. So books were always a big part of things. I grew up reading science fiction and fantasy novels and that sort of thing. Then, at a particular moment, my father started to—he was an administrator at Brigham Young University—and he started to read their general education books and got very interested in some of those and began to give some of those to me. I think the most important thing was when I was around 13 or 14 he brought home a copy of The Basic Kafka and sat down and read a story kind of with me and then talked about it and then gave me the book. That’s the moment I can really identify my reading habits as changing. So I went in the course of just a year or two from reading things like Roger Zelazny and Anne McCaffrey to reading Kafka and that led me to people like Beckett and those sorts of things. There was a decent used bookstore in Provo that just happened to have a lot of Grove Press books and so I just started reading basically Grove Press books. I started reading these books, mostly plays by people like Beckett and Ionesco, and who knows who else and that suddenly made me think about, it brought me in connection to the larger literary world. But I really just cobbled it together. I read things at random; I kind of made my own parameters, which was I was going to read everything that this press has done and went from there to reading other things. And that’s kind of the way I’ve constructed it, I’ve just read at random and allowed things to influence me just coming from wherever they come from.

AS: Did you ever feel a tension between the books you were reading and those religious texts that were also in your home?

BE: Yes, there was definitely tension. I think that the religious texts were pushing one thing and the literature I was reading was pushing another thing. I think The Book of Mormon is a complex and interesting book and the same with the other doctrinal books that Mormonism has. I think all the things that have built up around that, the books by Boyd K. Packer, the general authority sort of books are totally uninteresting and are really very much about softening whatever the Bible or the Book of Mormon can do to somebody. So I grew up thinking the literature I was reading was different from the Book of Mormon or the Bible but that there was a similar kind of approach to the complexity of the language or in some cases, the Bible in particular, the beauty of what was going on in the text or the kind of elusiveness or elision that was there. And that that was not something that was reflected in the broader Mormon culture as a whole. Buy at the same time it was very transgressive for me to read certain kinds of things. I remember reading Antonin Artaud, I kind of talk about this elsewhere, in the BYU library and finding him and being completely blown away by it and thinking as I’m reading that I’m going to go to hell for reading this, and just the intensity of that experience, the intensity of reading something that you respond to in that sort of way was really amazing.

BE: Yes, there was definitely tension. I think that the religious texts were pushing one thing and the literature I was reading was pushing another thing. I think The Book of Mormon is a complex and interesting book and the same with the other doctrinal books that Mormonism has. I think all the things that have built up around that, the books by Boyd K. Packer, the general authority sort of books are totally uninteresting and are really very much about softening whatever the Bible or the Book of Mormon can do to somebody. So I grew up thinking the literature I was reading was different from the Book of Mormon or the Bible but that there was a similar kind of approach to the complexity of the language or in some cases, the Bible in particular, the beauty of what was going on in the text or the kind of elusiveness or elision that was there. And that that was not something that was reflected in the broader Mormon culture as a whole. Buy at the same time it was very transgressive for me to read certain kinds of things. I remember reading Antonin Artaud, I kind of talk about this elsewhere, in the BYU library and finding him and being completely blown away by it and thinking as I’m reading that I’m going to go to hell for reading this, and just the intensity of that experience, the intensity of reading something that you respond to in that sort of way was really amazing.

AS: Do you remember which Artaud book it was?

BE: It was in English and it was four Artaud pieces: Artaud the Momo—the one that was most difficult for me is there was called “To Have Done With the Judgment of God,” which is a kind of play which ends with God being cut on the finger and his blood obliterating the stage. It was very weird. Very intense. I had this strange relationship to surrealism and absurd literature that was again, something I just stumbled on to and then kept reading.

AS: Since you brought up religious texts—have you read Harold Bloom’s The American Religion?

BE: Yes, I have.

AS: I’d like to read a short passage, Bloom’s writing about Joseph Smith, and hear your response. “Smith’s insight could have come only from a remarkably apt reading of the Bible, and there would locate the secret of his religious genius. He was anything but a great writer, but he was a great reader, or creative misreader, of the Bible . . . Joseph Smith’s alternative text—the Book of Mormon, the Pearl of Great Price, and the Doctrine & Covenants—are all stunted stepchildren of the Bible . . . all Mormon Scripture is the work of Joseph Smith, and his life, personality, and visions transcended his talents at the composition of divine texts . . . What moves me, here and elsewhere in Smith, is the sureness of instincts, his uncanny knowing precisely what is needful for the inauguration of a new faith. Like Saint Paul . . . Smith implicitly understood not only his own aims but the pragmatics of religion making, or what would work in matters of the spirit” (Bloom 81-81). What strikes me about this is the idea, and idea that was difficult for me for a long time, is thinking about Mormonism as something that was created by someone.

AS: I’d like to read a short passage, Bloom’s writing about Joseph Smith, and hear your response. “Smith’s insight could have come only from a remarkably apt reading of the Bible, and there would locate the secret of his religious genius. He was anything but a great writer, but he was a great reader, or creative misreader, of the Bible . . . Joseph Smith’s alternative text—the Book of Mormon, the Pearl of Great Price, and the Doctrine & Covenants—are all stunted stepchildren of the Bible . . . all Mormon Scripture is the work of Joseph Smith, and his life, personality, and visions transcended his talents at the composition of divine texts . . . What moves me, here and elsewhere in Smith, is the sureness of instincts, his uncanny knowing precisely what is needful for the inauguration of a new faith. Like Saint Paul . . . Smith implicitly understood not only his own aims but the pragmatics of religion making, or what would work in matters of the spirit” (Bloom 81-81). What strikes me about this is the idea, and idea that was difficult for me for a long time, is thinking about Mormonism as something that was created by someone.

BE: But there is a kind of creative genius to it, wherever you end up locating that genius. His ability to pull things together from very different, very weird sources. He’s drawing on stuff that was being discussed and talked about in New York at the time he was doing things. But there’s also this weird incorporation of stuff from the Masonic tradition. If you see it as something as fabricated, which at this point I do, it’s this huge act—this very impressive act. I have this colleague who does this exercise with her class where she asks them to imagine a new religion. It’s interesting, some students get into a very strange space with that, but most students can’t. Most students, when they imagine a new religion, imagine something that’s exactly the same as every other religion. And Mormonism, for all it’s flaws and faults, it’s pretty unique is my sense. It’s a very strange religion and kind of interesting. I think that what’s happened with Mormonism in the last 20 years—the changing of the temple ceremony and of moving into Middle America, and the kind of advertising of Mormonism has really done a lot to counteract that uniqueness of it, which for me, is maybe the only appealing thing about it.

tradition. If you see it as something as fabricated, which at this point I do, it’s this huge act—this very impressive act. I have this colleague who does this exercise with her class where she asks them to imagine a new religion. It’s interesting, some students get into a very strange space with that, but most students can’t. Most students, when they imagine a new religion, imagine something that’s exactly the same as every other religion. And Mormonism, for all it’s flaws and faults, it’s pretty unique is my sense. It’s a very strange religion and kind of interesting. I think that what’s happened with Mormonism in the last 20 years—the changing of the temple ceremony and of moving into Middle America, and the kind of advertising of Mormonism has really done a lot to counteract that uniqueness of it, which for me, is maybe the only appealing thing about it.

AS: This idea of the Mormon narrative. On the one hand, there’s a kind of gauge for appropriateness for Mormons in terms of their art. Your work has been deemed inappropriate by many of those people, especially the higher-ups. And at the same time in the Mormon narrative that Smith created there is all kinds of violence, transgressive sexuality and things like that. Have you ever thought about the ways your work has been influenced by those elements as found in the Mormon narrative?

BE: I have. When was writing Almann’s Tongue I don’t think I thought about it. But shortly after Altmann’s Tongue was published, I wound up doing an opera libretto for somebody who was trying to do an opera on the life of Joseph Smith. And going back and reading The History of the Church, those volumes, and seeing the kind of pathology that’s built up there, but also the kind of incredible violence in Smith’s own sense that he was going to die and the kinds of dreams he was having and things like that. There is this incredible intensity of violence that’s involved there. So when I did the libretto I focused on that. I also think those were things that growing up were minimized but very present to me. I knew a lot of the old frontier stories, I knew about Porter Rockwell, and about the Mormon massacre, and they were always presented as things that were not appropriate to talk about or that were below the surface but yet you still kind of knew about them. So you knew about these various massacres that have occurred even if you didn’t quite know the details and you knew the kind of structure of denial that went along with that. I think for me the other thing that was important was when I was pretty young the Laffretys were being convicted for crimes, for the blood sacrifice thing they decided to reinstitute and just thinking about how Mormonism is something that does allow itself to be misread in those ways was definitely important to me.

BE: I have. When was writing Almann’s Tongue I don’t think I thought about it. But shortly after Altmann’s Tongue was published, I wound up doing an opera libretto for somebody who was trying to do an opera on the life of Joseph Smith. And going back and reading The History of the Church, those volumes, and seeing the kind of pathology that’s built up there, but also the kind of incredible violence in Smith’s own sense that he was going to die and the kinds of dreams he was having and things like that. There is this incredible intensity of violence that’s involved there. So when I did the libretto I focused on that. I also think those were things that growing up were minimized but very present to me. I knew a lot of the old frontier stories, I knew about Porter Rockwell, and about the Mormon massacre, and they were always presented as things that were not appropriate to talk about or that were below the surface but yet you still kind of knew about them. So you knew about these various massacres that have occurred even if you didn’t quite know the details and you knew the kind of structure of denial that went along with that. I think for me the other thing that was important was when I was pretty young the Laffretys were being convicted for crimes, for the blood sacrifice thing they decided to reinstitute and just thinking about how Mormonism is something that does allow itself to be misread in those ways was definitely important to me.

AS: In your 1994 interview with Ben Marcus, he asks the question: “If you were excommunicated, you could certainly discover, that suddenly, in the larger context of American culture, fewer powerful figures would feel particularly threatened or incensed by your work. You would simply be seen as one of many artists, rather than only one, and thereby face the more general indifference and dismissal of a different, larger segment of the country. Would your forced removal alter the focus of your writing?” I wonder how you would answer that question now.

BE: I don’t know. The first book Altmann’s Tongue I wrote not thinking of it as something connected to Mormon culture at all and really not thinking much about myself as a Mormon. I mean a lot of it was written or drafts of it were written when I was in various connections to Mormonism, but really I don’t think I thought about it very consciously. And then the book came out and it ended up having all this controversy in Utah and people objected to it and that made me really think about it much more than I had before. And then I’ve written since then a few things that are Mormon-themed or that take that issue on. So I don’t know. In essence, I think what’s happening now is I’m getting back to the place I was at with Altmann’s Tongue, I’m writing work that isn’t definitively connected or thematically connected to Mormonism, but that really does come out of some kind of subconscious that is connected to the way I grew up as well as connected to other things beyond that.

AS: Do you think you can ever completely leave Mormonism behind in your work?

BE: I don’t know. I think all my work is very elusive, but the allusions are really hidden. And I think if you’re Mormon you feel those things a lot more and I do think there’s a certain way of speaking, ways that Mormons speak when they’re leaders or when they speak from the pulpit that’s in the work that is incorporated in ways that I don’t know that I fully understand but that’s definitely a part of it. I guess that’s what I would say. What is it? You can take the boy out of Mormonism, but you can’t take Mormonism out of the boy. It’s always going to be something there. It’s not there for me as an external religious structure at this point. When I left Mormonism I was terrified of leaving Mormonism. I thought it would be very difficult; I thought I would go to hell. And it actually has, all the way up to the point where I left it was difficult, but once I was actually out it was an incredible relief. And I think that part of what I’ve been doing since I left Mormonism is trying to figure out how to acknowledge where I came from and what my roots are and what the connections are there and to what degree that’s something that is connected to my children, who are being raised Mormon by their mother, by my ex-wife. But also being able to separate that from who I am now, acknowledging it as a comfortable part of who I am now, but not thinking I have to be overtly Mormon. Does that make sense?

AS: It does make sense, thank you. If I might pivot here: I have two questions I’ve always wanted to ask you. The first one is: When you were writing Altmann’s Tongue and you were in the bishopric, did you really think that these stories would go unnoticed?

BE: In the interview you quoted from, Ben Marcus talks about the general indifference of the larger population and I just thought the stories wouldn’t really be noticed. When the stories appeared in magazines no one in the Mormon church had noticed. I thought well, I’m writing for a literary world. And I think I was very good—and I think this is true of a lot of Mormons—at compartmentalizing different parts of my life. So I could think, here’s my church life, here’s my writing life, here’s my family life, here’s my school life and I could see connections between those things. But imagining that a book from my writing life would really have a huge impact on my family life or on my church life was hard to imagine in some ways. Having said that, I typed most of those stories on the computer up at church and printed them out there. That was where I could do that and our computer at home was so bad. I also, when I applied for Brigham Young University, one thing I asked them straight out was is it going to be a problem that I’m publishing these stories. So it was enough of a concern that I asked about it. Their response was, well, what’s going on in these stories? Is there sex in the stories? And I said, well, no, there’s not sex. There’s a lot of violence, but there’s no sex. And they said, well, if it’s only violence then that’s not a big deal. And it turned out not to be the case. So I was a little concerned, maybe, but I thought that I had a sense going in that people wouldn’t pay attention or know about it.

AS: The other question I’ve always wanted to ask is—and this extends to all writers really—I know you’ve talked about those moments when you had to decide between writing and something else and you’ve chosen writing. Is it really a choice? Can you stop writing? Can you write differently than you do? Is it a conscious choice, for example, to represent violence in the way that you do? Or is it so much a part of you that to not do it would basically be not to live?

BE: I think it would have been disingenuous for me to take another path. At the same time I do feel like there was a choice and that at a particular moment I realized that I’m writing my way out of the church, I’m writing my way out of this marriage and that’s something that ends up informing and compelling the writing. So in that sense, choosing to recognize that what the writing is doing to the other parts of your life ends up becoming, maybe that’s just the choice. Doing it consciously. Deciding to do it anyway. I think I’m the kind of person who probably if I lived my life over again I would make exactly the same mistakes even if I was conscious of how they’d been mistakes. So I don’t know. I think there is a level of agency. Having said that, I think that agency is definitely impacted by how one is formed, that if I was to write different sorts of fiction, which is what BYU wanted me to do—either stop writing or write very different kinds of stories—it would either (I think they would be terrible, first of all) and I also think it would just not be like writing for me. It seems like I’m sidestepping that a little bit. I feel compelled to write the way I do, but at the same time I think you do make a choice about it and I can see even within that format I think that there are little choices you’re making along the way. There have been particular points when I felt like, well, maybe I’ll just write certain kinds of things but keep them to myself and not publish them but I’ve made the choice to publish them. There are pieces I’ve published in magazines that I’ve chose not to collect for various reasons, mostly because I just don’t like them enough, but there is at least one piece for a moral reason I’ve chosen not to ever collect.

BE: I think it would have been disingenuous for me to take another path. At the same time I do feel like there was a choice and that at a particular moment I realized that I’m writing my way out of the church, I’m writing my way out of this marriage and that’s something that ends up informing and compelling the writing. So in that sense, choosing to recognize that what the writing is doing to the other parts of your life ends up becoming, maybe that’s just the choice. Doing it consciously. Deciding to do it anyway. I think I’m the kind of person who probably if I lived my life over again I would make exactly the same mistakes even if I was conscious of how they’d been mistakes. So I don’t know. I think there is a level of agency. Having said that, I think that agency is definitely impacted by how one is formed, that if I was to write different sorts of fiction, which is what BYU wanted me to do—either stop writing or write very different kinds of stories—it would either (I think they would be terrible, first of all) and I also think it would just not be like writing for me. It seems like I’m sidestepping that a little bit. I feel compelled to write the way I do, but at the same time I think you do make a choice about it and I can see even within that format I think that there are little choices you’re making along the way. There have been particular points when I felt like, well, maybe I’ll just write certain kinds of things but keep them to myself and not publish them but I’ve made the choice to publish them. There are pieces I’ve published in magazines that I’ve chose not to collect for various reasons, mostly because I just don’t like them enough, but there is at least one piece for a moral reason I’ve chosen not to ever collect.

AS: You’ve had to justify and characterize your work as much as any writer I know of, at least in the U.S. recently. Has that hindered or changed your writing process at all?

BE: I think it’s made me more careful about what I do, but I don’t think it’s made me—I think a lot of what you do when you’re talking about your own work is you’re constructing what you think you might have done after the fact. And so, for me there is something very artificial about that. I mean there are certain ways of explaining the work, for getting into the work, but I think there are a lot of different things I could talk about. There are probably reasons that I write or reasons that my work does particular things I just don’t clearly understand or can’t articulate. So those explanations are always pretty limited. I think in a way that if you’re pretty articulate about being able to talk about why you do what you do, in some sense that’s a limitation because it’s more convincing than if your inarticulate and so it kind of pushes readers toward reading it in a certain way. But yes, I feel like I constantly have had to justify or think about why I do what I do and I think for me as a writer that’s good. I think if the writing becomes a matter of trying to prove something then it’s a problem and I’ve tried to avoid that, to keep it from being writing that has a thesis and I want to express it. For me, I guess one of the big things I’m interested in writing itself is the intensity of it and getting to a point—I do see it as experiential—you’re experiencing something as you read it. I want the reader to go through something and for that something to be something that has an effect on them. And that’s something you really can’t explain. I mean that’s something you can talk about, but I can’t explain how those effects are achieved or why I want that.

AS: Is it possible for you to experience your stories the way a reader might?

BE: Yes, you think about it somewhat. And I mean I read enough that I think I know how certain kinds of readers approach stories. I read a lot. And as I’m reading I’m thinking about how things are put together and how they create an effect. Sometimes it’s true that the reason some people like certain of my stories is because they understand them in a very different way than I understood them when I was writing them. We’ve talked privately, you and I, about the way in which being a Mormon reader of my work postulates you very differently, I think, than being a wider, world reader, or whatever you want to call it, non-Mormon reader. So definitely, I think there’s a range of possibilities. The work is something that can serve as a catalyst. The reader is always bringing something to the work. But I think I direct those choices that the reader can make and limit them in certain ways. Yes, but I can’t predict how people are going to take the work.

AS: Your former colleague, John Bennion, from BYU, wrote an article called “Reading and the distance between New York and Utah,” in which he writes: “Mormon writers, in order to succeed with a national literary audience must: abandon certain Mormon conventions, especially the assumption of universal truth, resist a yearning for textual closure, the same textual closure Mormon readers often swaddle themselves in, accept dissonance in language, and violate central Mormon premises.” So there’s this problem of double-audience for a Mormon writer. It is as if to write for one audience is to alienate the other. What was your notion of audience when you started writing?

AS: Your former colleague, John Bennion, from BYU, wrote an article called “Reading and the distance between New York and Utah,” in which he writes: “Mormon writers, in order to succeed with a national literary audience must: abandon certain Mormon conventions, especially the assumption of universal truth, resist a yearning for textual closure, the same textual closure Mormon readers often swaddle themselves in, accept dissonance in language, and violate central Mormon premises.” So there’s this problem of double-audience for a Mormon writer. It is as if to write for one audience is to alienate the other. What was your notion of audience when you started writing?

BE: I was writing for a larger, literary audience. That was my notion—that I was writing for the larger world out there. I’ve always been skeptical of universal truth, even when I was Mormon, both in life and in literature. And I’ve always been skeptical of closure as well. So I think that literature I something that shouldn’t provide neat packets of information. I think that Mormonism in general has thought of literature as a didactic experience, that it’s something that is there to learn from. I have nothing against thinking that you can learn something from literature but I don’t think it’s there to inflict these moral lessons upon us. I think it’s much more complicated than that. So I guess that’s what I would say, that literature is not strictly mimetic, that literature is not there just to provide a mirror for life. There’s something else going on. And that something else has something to do with affect, it has something to do with experience, something to do with the way the mind works. There’s lots of other things going on there.

AS: Do you think it’s possible to be both a good artist and a good Mormon? What I mean by good artist is someone that does resist that closure, universal truth, those things that Bennion mentions. Because I think good art has to resist those things.

BE: I personally don’t think so. I began thinking that was possible. I began thinking that I could kind of compartmentalize things, that I could live in a particular way, that the literature was doing something else. And certainly growing up I felt like I had no problem going to church on Sundays and reading certain kinds of books during the week. I really felt that way up to when I was in a bishopric in Seattle and I was taking Marquis de Sade class at school and on Sunday I was meeting with people talking about their problems. That didn’t seem like a contradiction to me. It seemed like anything was okay. In retrospect I can see how that would seem totally crazy to people. And ultimately it’s not something that really you can keep up or that people will let you keep up if they know that that’s how you’re thinking about the world. So I don’t think it’s possible to be a good artist and a good Mormon at the same time. But I think that has less to do with the individual than it does with the institution of the church. And it has less to do with the doctrine than it does with the institution. Yes, I think it’s very difficult.

AS: I agree. I wondered if you can talk for a minute about the role of women characters in your work. Because there aren’t many.

BE: It’s true. There’s a lot more men. A lot of the stories are very much about patriarchy and kind of an imploding patriarchy. And very much about a kind of violence that’s involved in that. For a long time I tried to think about my work as having an affinity to feminism in the sense that it was about the kind of dark side of patriarchy. Maybe it’s not as simple as that, but it definitely is true that, and I think this is part of growing up Mormon, men and power are really a big part of the work itself. In terms of the women, the other thing I would say is that there is an equal-opportunity violence so that people are being murdered, but it’s men and women both. I don’t think that always ends up directed towards women. There are stories like stung in Altmann’s Tongue in which there is a woman in a very weird position of power and there’s something very creepy about that as well, but there’s also a kind of inversion of what’s been going on in the other stories. Most of the worlds in the stories are not very pretty worlds. So I don’t know. It’s a difficult question. I wonder about this a lot.

BE: It’s true. There’s a lot more men. A lot of the stories are very much about patriarchy and kind of an imploding patriarchy. And very much about a kind of violence that’s involved in that. For a long time I tried to think about my work as having an affinity to feminism in the sense that it was about the kind of dark side of patriarchy. Maybe it’s not as simple as that, but it definitely is true that, and I think this is part of growing up Mormon, men and power are really a big part of the work itself. In terms of the women, the other thing I would say is that there is an equal-opportunity violence so that people are being murdered, but it’s men and women both. I don’t think that always ends up directed towards women. There are stories like stung in Altmann’s Tongue in which there is a woman in a very weird position of power and there’s something very creepy about that as well, but there’s also a kind of inversion of what’s been going on in the other stories. Most of the worlds in the stories are not very pretty worlds. So I don’t know. It’s a difficult question. I wonder about this a lot.

AS: So it’s just sort of happened?

BE: No, I’ve thought about it, but it’s something that—my work is so much of a critique of patriarchy and critique of religious patriarchy that that’s part of it. And so with something like Father of Lies, the roles of women are very much dictated by the structure of the religion itself. In The Brotherhood of Mutilation it’s almost all men. There’s a brief appearance of a woman and she’s kind of a reduce woman in some ways which I think says something about religion and women as well. It’s no coincidence, by the way, that The Brotherhood of Mutilation has the same initials as The Book of Mormon. And then in The Wavering Knife there are women that appear from time to time. In terms of thinking whether or not I provide positive role models for women? I don’t think I do. I don’t think I really do for men either.

BE: No, I’ve thought about it, but it’s something that—my work is so much of a critique of patriarchy and critique of religious patriarchy that that’s part of it. And so with something like Father of Lies, the roles of women are very much dictated by the structure of the religion itself. In The Brotherhood of Mutilation it’s almost all men. There’s a brief appearance of a woman and she’s kind of a reduce woman in some ways which I think says something about religion and women as well. It’s no coincidence, by the way, that The Brotherhood of Mutilation has the same initials as The Book of Mormon. And then in The Wavering Knife there are women that appear from time to time. In terms of thinking whether or not I provide positive role models for women? I don’t think I do. I don’t think I really do for men either.

AS: The most powerful woman, it seems, is the woman in Dark Property. The one who throws the stones.

BE: She has a role where she fights back and she does have a kind of power that the man (Kline) who ultimately becomes very bound to her respects her in a way. And that’s true in The Open Curtain. A third of the book is third person, but from a woman’s perspective and she’s someone who is very much caught inside a religion in the same way that the men in the book are. But she ultimately is put in a position where she potentially can kind of escape, but it’s left without that resolved. I think about this a lot. I would like to think that they’re not sexist stories, but it may be true that I sometimes play into certain types. But I try to resist that.

AS: The study I’m doing—it’s come down to Mormon-American Men writers. There are these extreme representations. The violence in your work, for instance. Or in Neil LaBute’s work there’s misogyny and misanthropy. Timothy Liu has some extremely sexual poetry. And even Levi Petersen in The Backslider, there are some extreme scenes of masochism—the castration scene, for example. It seems to have to connect to patriarchy and the power structures in the Mormon church, but I’m not sure how.

BE: I do think it connects. I think in LaBute especially. I see it as very connected. There are, in most of his plays and movies, these power games that go on, largely between men that are very often homoerotic power games in which the women are seen as chips almost. And I do think that Mormonism, and patriarchal religion in general, do put people in that position, especially women. That’s how I think it’s connected. We talk in Mormonism about, or they talk in Mormonism I should say now, about putting women on a pedestal and things like that, and that seems to me just the other side of that. That there something very menacing about that.

AS: Have you thought of yourself as a part of the Mormon literary canon? Is there such a thing at all?

AS: Have you thought of yourself as a part of the Mormon literary canon? Is there such a thing at all?

BE: The difficulty with the Mormon literary canon is figuring out who is making the canon. There are things the Association for Mormon Letters (AML), but I think often their taste in books is pretty bad. I think this is something that anytime you’re talking about literature being arranged according to a culture or an ethnicity in the early stages of that people just really collect all the stuff that really fits—they’re just desperate for a sense of identity. And so the things that often get the focus are the things that seem most overtly to be in that category. So The Association for Mormon Letters ends up praising books that are often quite bad. So in that sense I don’t feel all that connected to it. I do feel connected to other writers who I know are Mormon, most of whom have left the church at this point. People like Neil LaBute, Darrell Spencer to some degree, Derek Gullino who only published four or five stories a few years ago. And then a few other people like that. I thought that Jesus Rodriquez was doing some interesting things at a particular moment. There are people like Tim Liu, who even though are world views are different, I still think he’s very interesting as a writer. Those are the people I’m interested in, the people who are kind of on the edge or the fringe and looking back in. It’s partly, I think, because Mormon culture is young enough that it takes someone on the fringe to really be able to give it an honest look. Cultures go through various stages and one stage they go through is kind of an expansiveness, and they get nervous about how much they are expanding. And that I think is what’s happened with Mormonism, that there is an attempt to control things and shut things down. So the writers who are most interesting are people who are outside the official structure and who are willing to take some risks. I think that they’re the ones that are saying the most interesting things about Mormonism. For years when I was at Brigham Young University, people would talk about the great Mormon novel and who would write it, but their notion, when I started talking to them about it, their sense of what it would take, is that you’d still be very much within the guidelines of the church. It would still promote all the church values. So it’s like the great official Mormon novel in the same way that like—it would be like Soviet literature. That just doesn’t seem viable to me. Where it gets especially tricky with Mormonism is that you have parts of the Mormon church that are not talked about, kept secret or sacred or whatever you want to say. And then how do you really express much about the culture if there’s this whole hidden aspect of it?

AS: There has been a tradition in ethnic literature, when writers reveal the secrets of the group, then they are cast out. It may not be a formal excommunication, but the effects are often the same. In Mormonism I think this is just starting to happen—particular writers like you, LaBute, and Liu are bubbling up. And it’s interesting that the three of you were all at BYU at the same time.

BE: There were a bunch of us that were there around the same time. David Valas was there too who went on to do screenwriting in Hollywood and direct some things. There were a few people. There was a moment where things were starting to bubble and where we were informing one another. And it’s interesting how many of those people have gone on to at least publish some nationally. I’ve talked about this with Gordon Lisch too because there was a moment when he realized he was publishing a lot of Mormons in his magazine The Quarterly and his sense is that if you have a culture that puts people under a kind of intense pressure then it either destroys them or it galvanizes them in a way that something interesting comes out. I think there is much more potentially at stake for you if you’re a writer and Mormon than there would be just being a writer in the larger American culture or in a different sort of culture. I have a friend who is a writer who is also Amish and he has a similar kind of feeling because of the intensity of the culture he comes from.

BE: There were a bunch of us that were there around the same time. David Valas was there too who went on to do screenwriting in Hollywood and direct some things. There were a few people. There was a moment where things were starting to bubble and where we were informing one another. And it’s interesting how many of those people have gone on to at least publish some nationally. I’ve talked about this with Gordon Lisch too because there was a moment when he realized he was publishing a lot of Mormons in his magazine The Quarterly and his sense is that if you have a culture that puts people under a kind of intense pressure then it either destroys them or it galvanizes them in a way that something interesting comes out. I think there is much more potentially at stake for you if you’re a writer and Mormon than there would be just being a writer in the larger American culture or in a different sort of culture. I have a friend who is a writer who is also Amish and he has a similar kind of feeling because of the intensity of the culture he comes from.

AS: When you brought up AML it made me think of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought too. One thing I’ve noticed in my research, and one thing I’m trying to work against, is that kind of protectionism and isolationism in Mormon literary studies. You’ve got these mechanisms in place. Dialogue, for instance, defines its audience is just a Mormon audience. In the John Bennion article, for example, he does a lot of really great work, but in the end, he makes it Mormon. And the great Mormon novel, as you said, as long as it conforms to Mormon truth.

AS: When you brought up AML it made me think of Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought too. One thing I’ve noticed in my research, and one thing I’m trying to work against, is that kind of protectionism and isolationism in Mormon literary studies. You’ve got these mechanisms in place. Dialogue, for instance, defines its audience is just a Mormon audience. In the John Bennion article, for example, he does a lot of really great work, but in the end, he makes it Mormon. And the great Mormon novel, as you said, as long as it conforms to Mormon truth.

BE: There is this attempt, even the sources that try to take literary issues seriously—on the one hand you have Dialogue that does try to wrap things up into a Mormon theme. The articles are relatively serious, but not completely serious. I don’t know if that is what you feel too.

AS: Yes.

BE: There are these gestures that are scholarly that go on, but then there’s this other thing that keeps on invading. Then on the other hand, you have something like Sunstone where there is a particular stance as well to inform everything, and that stance has something to do with being skeptical and kind of outside of Mormonism, but being outside of it in a particular way and still kind of being friendly to the church. I don’t know. It’s a complicated issue. Sunstone is a far cry away from the friend, but there’s still something suspect about that. The work hasn’t been done yet to really think seriously about Mormon literature, even like just a particular moment in Mormon literature. There’s been historical work done that’s really interesting, but that’s all I know of. I think it’s interesting to think of Mormon literature as being connected to ethnic literature. Even though it’s very tricky in some ways because Mormonism is always bringing in new people and there is a kind of constant sense of change. But I also think that there is something very particular about being raised Mormon. And even when you have converts, they don’t get that.

BE: There are these gestures that are scholarly that go on, but then there’s this other thing that keeps on invading. Then on the other hand, you have something like Sunstone where there is a particular stance as well to inform everything, and that stance has something to do with being skeptical and kind of outside of Mormonism, but being outside of it in a particular way and still kind of being friendly to the church. I don’t know. It’s a complicated issue. Sunstone is a far cry away from the friend, but there’s still something suspect about that. The work hasn’t been done yet to really think seriously about Mormon literature, even like just a particular moment in Mormon literature. There’s been historical work done that’s really interesting, but that’s all I know of. I think it’s interesting to think of Mormon literature as being connected to ethnic literature. Even though it’s very tricky in some ways because Mormonism is always bringing in new people and there is a kind of constant sense of change. But I also think that there is something very particular about being raised Mormon. And even when you have converts, they don’t get that.

AS: Right. I’ve tried to explain to people that there are different kinds of Mormons. A Utah-Mormon. A U.S. Mormon. A Dutch Mormon.

BE: I think it’s very different to be Mormon if you’re Mormon in another culture. But that particular combination of Mormon religion with frontier culture and the way in which that developed into a kind of mode.

AS: One of the distinguishing characteristics of Ethnic literature, and even American literature, is the way certain groups have othered themselves and separated themselves and Mormonism is a great example of this. The belief system, the culture, the way they moved west.

BE: I think it’s hard to explain this to someone who has not been in the culture. When I was in Utah recently I talked to a guy who teaches at the University of Utah and hasn’t been there for very long and his sense of it is: Utah and Mormonism there is like all the clichés you have about the old west in terms of the friendliness and in terms of the kind of closed-ness at the same time, etc. He said, but you know, it doesn’t exist anywhere else but here anymore. It’s definitely there. It’s definitely based in a place. It’s definitely predominantly based in a type of people. It’s something that you find curiously enough in people who were raised Mormon but are no longer Mormon. You don’t find it in someone who converted to Mormonism after the age of 16 or so. And so there is something very much about that.

*